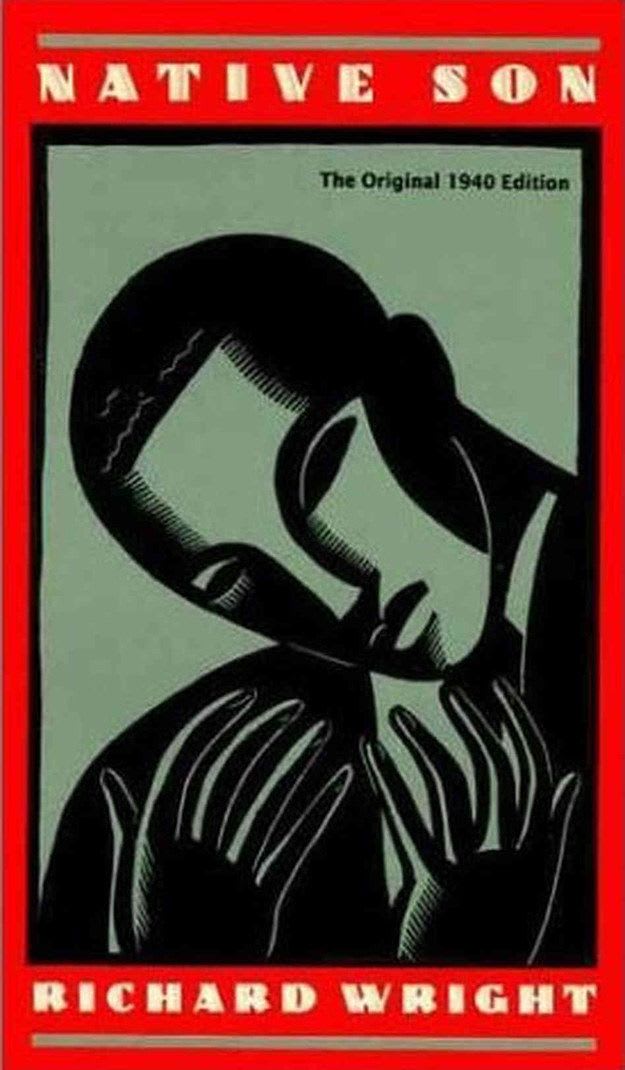

Native Son and the Immigrant Woman: Seen, Unseen, and Surviving

Because no one should have to fight to be seen as fully human in a place they call home.

Richard Wright’s Native Son is often read as a story about race, fear, and systemic oppression. But beyond Bigger Thomas as a character, the novel is really about what happens when society decides who belongs; and who does not.

In many ways, this question of belonging is one immigrant women understand deeply.

Bigger is called a “native son,” yet he moves through his own country as an outsider. His fear is not imagined; it is learned. Every space he enters reminds him of limits placed on his body, his choices, and his future. This tension; being physically present but socially excluded; mirrors the experience of many immigrant women today.

Immigrant women may arrive in a new country with hope, qualifications, and resilience, yet find themselves confined by invisible walls: accents that are judged, credentials that are dismissed, labor that is undervalued. Like Bigger, they are often defined before they are known.

What Native Son exposes is how systems shape identity. Bigger’s actions are constantly interpreted through stereotypes imposed on him. Similarly, immigrant women are frequently reduced to labels: “the foreigner,” “the caregiver,” “the domestic worker,” “the undocumented.” These labels erase complexity, humanity, and individual stories.

Yet there is a quiet strength immigrant women carry that the novel helps us recognize by contrast. While Bigger reacts to a world that has denied him agency, many immigrant women are forced to adapt strategically; to survive not through confrontation alone, but through endurance, sacrifice, and reinvention. They learn new languages. They raise families across borders. They build lives in places that do not always welcome them.

Native Son also challenges readers to examine responsibility not just individual responsibility, but societal responsibility. Wright forces us to ask uncomfortable questions: What kind of society creates fear as a default emotion? What systems push people to the margins and then punish them for being there?

For immigrant women, these questions are not theoretical. Policies, workplaces, healthcare systems, and social attitudes shape daily realities. When support systems fail, the burden often falls disproportionately on women; especially those navigating immigration alongside motherhood, caregiving, or economic hardship.

Reading Native Son today, alongside immigrant women’s stories, reminds us that exclusion is never accidental. It is constructed. And so is belonging.

If literature has power, it is in its ability to make us see. To recognize that the “other” is not distant, but present. That the struggle for dignity-whether of a Black man in 20th-century America or an immigrant woman today-is deeply connected.

Because no one should have to fight to be seen as fully human in a place they call home.